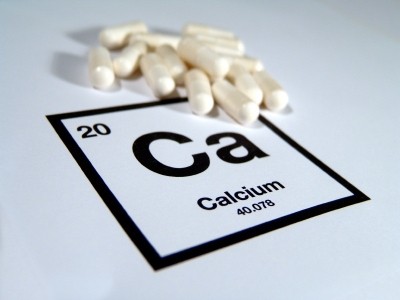

Calcium may not help prevent bone loss in men

Increased dietary calcium intake did not significantly reduce bone loss in the hip, spine or total body in a group of men aged 39-88, reported the research team from University of Auckland.

No correlation was observed between calcium intake and BMD either at baseline, or at the end of the study period. Although dietary calcium intake was inversely related to parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels at baseline, indicators of bone turnover were uncorrelated with calcium intake.

“Bone loss over 2 years was not related to Ca intake at any site, before or after adjustment [forconfounding variables],” wrote first author, Dr. Sarah Bristow.

“Dietary calcium intake was inversely correlated with PTH at baseline, but was not associated with the markers of bone turnover.”

The findings may have important implications for osteoporosis prevention strategies, where increased dietary or supplemental calcium intake has previously been recommended.

“This suggests that efforts to increase calcium intake are unlikely to have an impact on the prevalence of and morbidity from male osteoporosis,” the researchers propose.

“Many of the messages being promulgated at the present time are based on the findings of calcium-balance studies and the short-term effects of high-dose calcium interventions, which do not reflect those of long-term dietary intake.

“Messages to increase dietary calcium could be directing at-risk individuals away from considering interventions and strategies proven to influence long-term fracture risk.”

Study detail

The study used data from a previous Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) which examined the effect on BMD in 323 males given either 1200 milligrams/day (mg/d), 650 mg/d or placebo of calcium over two years. Data from the placebo group (n=99) were used in longitudinal analysis.

Although the earlier RCT found that the 1200 mg/d dose improved BMD by around 1%, this effect was achieved in the first 6 months, with no further subsequent improvement in the remaining 18 months.

These results prompted the researchers to hypothesise that short-term calcium intakes from high-dose calcium interventions are unrepresentative of longer-term dietary intake. The findings of the recent longitudinal study support this hypothesis.

They are also consistent with previous research indicating a similar lack of association between calcium intake and bone loss in women.

Contradictory results?

The researchers suggested the lack of association between calcium intake and BMD might be because the body is able to maintain calcium homeostasis over (long-term) typical dietary ranges (415-1740 mg/d).

Observational study findings appear to contradict supplementation RCTs, which have shown small increases in BMD, coupled with reductions in PTH and bone turnover. However, BMD improvements identified in RCTs have only occurred in the first year with no further cumulative effect.

This may be because short-term high doses of calcium induce a temporary reduction in bone turnover, which does not persist once steady-state calcium homeostasis is restored, suggested the researchers.

“Collectively, evidence from intervention and observational studies suggests long-term calcium intake doesn’t influence the rate of bone loss, but large increases in calcium intake induce a transient change,” they wrote.

The scientists emphasised that the study was conducted in Caucasian males with adequate vitamin D status. Therefore, results may not be applicable to other ethnic groups or those with vitamin D deficiency.

“The present demonstration of an absence of an effect of dietary calcium intake on current bone mass or on bone loss in normal men, together with the absence of an effect of calcium intake on bone turnover, contributes to the body of evidence suggesting that calcium intake, within the range studied here, is not a critical factor in the maintenance of bone health in older adults” the authors concluded.

Source: British Journal of Nutrition

Volume 117, issue 10, pp 1432-1438. DOI: 10.1017/S0007114517001301

“Dietary calcium intake and rate of bone loss in men”

Authors: Sarah M. Bristow, Gregory D. Gamble, Anne M. Horne and Ian R. Reid