Knowledge of the importance of early life nutrition has increased significantly in recent years. While the main goal used to be feeding a baby enough to hit a predefined growth curve, scientific research is now revealing a nuanced picture of the nutrient levels that are needed from preconception through to postnatal, to ensure long-term development and health. For parents, this knowledge opens a new frontier in their attempts to give their children the best possible start in life.

The evolution of thinking about early life nutrition is underpinned by a succession of research papers that have added layers of complexity to understanding of what constitutes a healthy start to life. In doing so, researchers have revealed both the wisdom and weakness of the old adage about pregnant women eating for two.

Simply eating more may do more harm than good with respect to health of the baby in later life: disproportionate weight gain during pregnancy can be associated with the offspring developing metabolic and cardiac dysfunctions in adulthood. Pregnant women need to make sure to take on sufficient amounts of essential nutrients, without a corresponding jump in calorie intake.

Nutrition challenges for pregnant women and young mothers

Since the release of a landmark NIH-backed review on Weight Gain During Pregnancy in 2009, evidence has emerged that the messages it contained are yet to translate into a shift in early life nutrition. A review of pregnancy in the developed world showed many women are consuming suboptimal levels of micronutrients, notably folate, iron and vitamin D. In 2015, a separate study revealed similar shortfalls in nutrient intake in China. The effects of such nutritional deficits are significant and far reaching, with suboptimal levels of vitamin D alone being associated with various conditions such as preeclampsia or a child’s risk of obesity.

Work is underway to make it easier for women to apply the lessons of nutritional research to their own pregnancies. When it comes to nurturing newborns, mother nature has optimized the composition of breast milk to match the evolving nutritional needs of early development. Breast milk’s status as optimal nourishment is undisputed. It therefore also serves as the gold standard for formula development. Human milk is a highly effective way of providing babies with the growth factors, oligosaccharides, antimicrobial peptides and proteins they need to support the development of their immune system, gastrointestinal tract and brain.

Awareness of the importance of breast milk has led WHO to target an increase in the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months up to at least 50%. The goal is one of six global 2025 WHO targets to improve maternal, infant and young children nutrition. Between 2007 and 2014, only about 36% of infants aged 0 to 6 months worldwide had been breastfed exclusively.

Mother’s milk was found to protect babies from infections like pneumonia and diarrhoea, while also drastically reducing the likelihood of suffering from obesity and Type II diabetes later in life. Equally, breastfed children score higher on intelligence tests. For all mothers who cannot breastfeed as recommended, well formulated infant and follow-on milks are vital to the health of their babies.

The exact mix of nutrients needed by mothers and their babies at each step of development is an intensely studied and evolving subject. Vitamin D is widely seen as one cornerstone of a healthy start.

Vitamin D: A lesson in applied nutrition

How to prevent vitamin D deficiency is well known. The challenge comes in putting this knowledge into practice for early life nutrition. Deficiency is a problem in all parts of the world, despite the role of vitamin D in the prevention of rickets being among the most widely known aspects of nutrition. In the UK, the rate of hospital admissions related to rickets is at its highest since the 1960s.

This and other findings have finally led to action. In 2014, representatives from 11 international scientific organizations met to establish a global consensus on how to prevent nutritional rickets, leading to recommendations that pregnant women and infants take supplements of 600 IU and 400 IU of vitamin D a day, respectively.

In analyzing the evidence and coming up with a concrete, achievable recommendation, they have shown that it can be quite easy to prevent a nutritional problem when measures are put in place by the standard-setting community. As early life nutrition continues to grapple with putting academic findings into practice in the real world, this lesson will prove useful.

Metabolic programming: Expanding the possibilities of nutrition

Today, research is just starting to reveal the possible downstream effects of campaigns to improve early life nutrition. In the case of vitamin D, for example, the link between deficiency and rickets was established years ago. Now though, new evidence of the function of vitamin D is being uncovered in research, which has linked deficiency to preeclampsia and preterm birth, as well as long-term effects on the child, such as the risk of obesity and allergies.

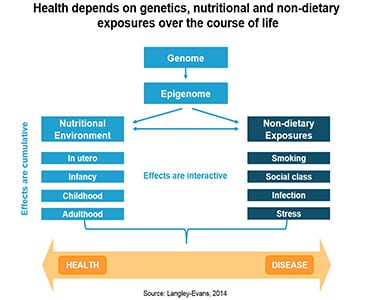

Evidence to support the hypothesis that early life nutrition is strongly tied to long-term health outcomes started to emerge in the late 1990s when researchers tracked down individuals whose births were logged between 1911 and 1948. The process revealed that babies born weighing 2.7 kg were 25% more likely to contract heart disease later in life than individuals who weighed 4.1 kg at birth. A similar trend was detected for the risk of having a stroke.

A subsequent study of 20,000 people born in Helsinki between 1924 and 1944 found the incidence of diabetes among the population later in life would have been halved if all the babies were in the top third of the birth weight range. In the years since these studies were published, researchers have uncovered more details about why early life nutrition affects long-term health outcomes. The work has created a more nuanced picture than the early correlations between birth weight and diseases.

Research has shown that the influences on health start far beyond birth. The ovarian follicles of obese women accumulate metabolites such as insulin, lactate and triglycerides in greater quantities than their peers who are of average weight. This shift in the makeup of the ovarian follicles has long-term consequences for obese womens’ children, who were shown to be at higher risk of developing diabetes, cardiovascular disease or cancer. The nutritional environment at the time of conception is tied to birth weight, too, a fact proven through in vitro fertilization.

The long-term consequences of nutrient availability continue throughout a pregnancy. When faced with adverse conditions in the womb, a fetus will prioritize the development of the most essential organs. Given that the kidneys and lungs are nonfunctional in the womb, it is rational for a fetus to divert the limited supply of nutrients to other organs. However, the smaller kidneys with fewer nephrons that result from this resource prioritization can lead to high-blood pressure later in life.

The role of the microbiome in lifelong health

Nutritional influences on the development of a fetus work in parallel to the effect of another force: the microbiome. Whereas the fetal intestine was once accepted to be sterile, studies have suggested that microbial colonization begins in the womb. Research has also shown that the load and composition of microbes changes during pregnancy. Work is needed to further understand the implications of these studies. However, given the growing recognition of the key role of the microbiome in lifelong health, they could be significant.

For example, there is growing evidence to support the hypothesis that obesity may be a communicable disease, passed from mother to offspring through bacterial transmission. While still unproven, there is now a plausible hypothesis based on the modulation of maternal systems, such as nutrient uptake. With other studies identifying correlations between early microbe colonization and conditions including allergies and autoimmune diseases, the full impact of the microbiome on health is only just emerging.

From an early life nutrition perspective, the findings hint at the potential to change long-term health outcomes through the use of probiotics, prebiotics and fermentation products to modulate the composition of the gut microbiota.

New tools to influence long-term outcomes

When paired with an emerging understanding of the long-term effects of substances such as vitamin D, microbiome research is driving a rethink of what can be achieved through applied nutrition. This extends to whether the scope of such initiatives should even expand to target men. It is now possible to foresee a future in which campaigns to change the diets of parents before conception improve long-term health outcomes in the next generation.

If the concepts currently at the vanguard of nutritional research develop as some predict, public health schemes will gain powerful new tools with which to influence long-term outcomes. Exactly how this plays out is unclear, but research suggests that, well-known nutrients like vitamin D will play a more prominent role in applied nutrition in the future and the significance and influence of the microbiome will continue to expand.

Excitingly, we are only just starting to glimpse how significant these factors could prove to be to the future of health.

This article is written by/on behalf of BASF Nutrition & Health and not by the NutraIngredients.com editorial team.