The 66-page report, produced by the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, and the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN), reveals the status of national laws to protect and promote breastfeeding.

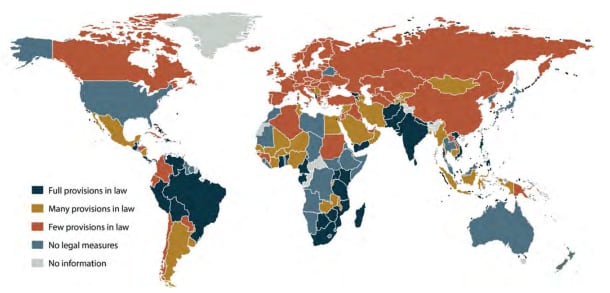

Of the 194 countries analyzed, 135 have in place some form of legal measure related to the 1981 International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes and subsequent, relevant resolutions adopted by the World Health Assembly (the Code).

This is up from 103 in 2011, when the last WHO analysis was carried out. However, only 39 countries have laws that enact all provisions of the Code—an increase of only two nations since 2011.

First six months should be breast milk only

WHO and UNICEF both recommend babies are fed nothing but breast milk for their first six months, after which they should continue breastfeeding—as well as eating other safe and nutritionally adequate foods—until two years of age or beyond, where possible.

WHO member states have committed to increase the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life to at least 50% by 2025.

The Code calls on countries to protect breastfeeding by stopping the inappropriate marketing of breast-milk substitutes (including infant formula), feeding bottles and teats.

According to the WHO, new studies have revealed that increasing breastfeeding to near-universal levels could save the lives of more than 820,000 children under the age of five and 20,000 women each year.

It could also inject an estimated $300bn into the global economy annually, based on improvements in cognitive ability if every infant was breastfed until at least six months of age and their expected increased earnings later in life. Boosting breastfeeding rates would significantly reduce costs to families and governments for treatment of childhood illnesses such as pneumonia, diarrhoea and asthma.

Formula only when necessary

The Code aims to also ensure breast-milk substitutes (BMS) are used safely when they are necessary. It bans all forms of promotion of substitutes for infants - including advertising, gifts to health workers and distribution of free samples.

In addition, labels cannot make nutritional and health claims or include images that idealize infant formula. They must include clear instructions on how to use the product and carry messages about the superiority of breastfeeding over formula and the risks of not breastfeeding.

The breast-milk substitute business is a big one, with the WHO saying annual sales amount to almost $45bn worldwide, rising more than 55% to $70bn by 2019.

One of the authors of the report, Dr Laurence M. Grummer-Strawn, technical officer, nutrition for health and development at WHO, told DairyReporter that neither the report, nor the Code, were against formula producers.

“Certainly, for the babies who can't breastfeed for some reason, if the baby has a physiological problem, or the mother cannot produce enough milk, then infant formula is absolutely necessary for the good health of that baby. So it does save lives. And in no way do we want to be seen as trying to get rid of this product,” Grummer-Strawn said.

“We want infant formula to exist. We want them to sell their products in a responsible way.”

Report findings

The report, Marketing of breast-milk substitutes: national implementation of the International Code – Status report 2016, includes tables showing, country by country, which Code measures have and have not been enacted into law. It also includes case studies on countries that have strengthened their laws or monitoring systems for the Code in recent years. These include Armenia, Botswana, India and Vietnam.

Overall, richer countries lag behind poorer ones. The proportion of countries with comprehensive legislation in line with the Code is highest in the WHO South-East Asia Region (36% – 4 out of 11 countries), followed by the WHO African Region (30% – 14 out of 47 countries) and the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (29% – 6 out of 21 countries). The WHO Region of the Americas (23% – 8 out of 35 countries); Western Pacific Region (15% – 4 out of 27 countries); and European Region (6% – 3 out of 53 countries) have lower proportions of countries with comprehensive legislation.

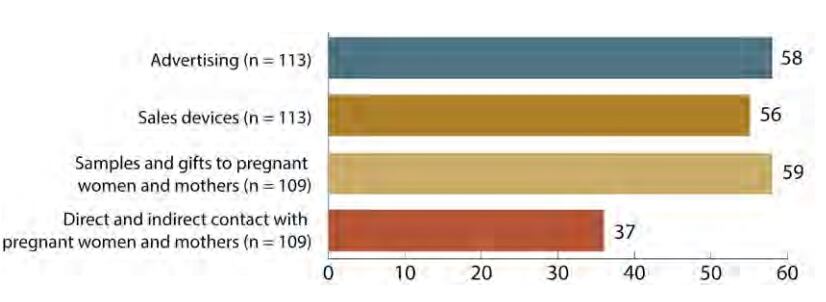

Among the countries with any laws on marketing of breast-milk substitutes, globally:

- Just over half sufficiently prohibit advertising and promotion.

- Fewer than half prohibit the provision to health facilities of free or low-cost supplies of breast-milk substitutes.

- Just over half prohibit gifts to health workers or members of their families.

- The scope of products to which legislation applies remains limited. Many countries’ laws cover infant formula and ‘follow-up formula’, but only one third explicitly cover products intended for children aged one year and up.

- Fewer than half of countries ban nutrition and health claims on designated products.

Monitoring and enforcement

The WHO says better market monitoring and enforcement is essential, yet only 32 countries report having a monitoring mechanism in place and, of those, few are fully functional.

Among the countries with a formal monitoring mechanism, fewer than half publish the results, and just six countries have dedicated budgets or funding for monitoring and enforcement.

Grummer-Strawn said a 55-country questionnaire revealed usually resource-strapped systems meant enforcement is generally poor.

"Only six of them actually had a regular funding source.

“Only seven of them had actually published the results of their last assessment, many of them had not done any assessments in the last three years, so while there are things on the books, and systems in place, they are not really very functional.”

Up against big companies, big budgets

While state systems may be under-funded, industry rarely is.

“That's exactly what we're up against," said Grummer-Strawn.

"The companies have large budgets. They do a lot of advertising, and we've noticed some places even when there are sanctions, they feel that they can just pay those sanctions and move on.

“It doesn't really change their behavior, because the amount is low enough relative to the budget that they have that they don't really care about the enforcement that is going on.”

He said that some companies go even further.

“We also know that they exert pressure on the political systems, whether that be in parliament when it's trying to enact a law, or it's on the government when it's trying to enforce the law. They exert their pressure to ensure weak implementation of the law.”

He added, “What we often find with industry is that they will give lip-service, ‘yes, we will comply with the code,’ but then you find many violations. You can see a good policy, but it doesn't get carried out in the actual marketing that happens.

“And many times even the policy itself, they'll find ways to weaken the policy, and say that it only applies in some countries, and it only applies in certain circumstances, only on some products, and they try to minimize how much of an impact that policy would have.”

Can’t match advertising

While multinational companies may have big advertising budgets, the WHO said it focuses on changing the environment "to be a more conducive environment to breastfeeding.”

WHO and UNICEF have established a Global Network for Monitoring and Support for Implementation of the Code (NetCode) to strengthen countries’ and civil society capacity to monitor and enforce Code laws. NGOs including IBFAN, Helen Keller International and Save the Children, academic centers and selected countries have joined.

Why breastfeed?

Globally, nearly two out of three infants are not exclusively breastfed for the recommended six months—a rate that has not improved in two decades, says the WHO.

According to the report, breast milk is the ideal food for infants:

- It contains antibodies that help protect against many common childhood illnesses

- Breastfed children perform better on intelligence tests

- Breastfed children are less likely to be overweight or obese

- Breastfed children are less prone to diabetes later in life

- Women who breastfeed have a reduced risk of breast and ovarian cancers

Toddlers

The older infant market was also on the radar for concern.

“Many countries have put in place legislation to look at the first six months of life, sometimes the first 12 months of life, so what companies are doing is they are creating products for a 12-month-old that they can market to expand their sales, but they make that product look very much like infant formula, and so there's a cross-promotion of the products for younger children as well.”

Grummer-Strawn said that he doesn’t expect the report is going to change things on its own, but it is a matter of consistently getting the important messages out and changing the way people think about the issue.

“We've normalized the use of infant formula so much that everyone thinks, ‘what does it really matter?’ The more we can use reports like this to get the message out, that this is not crazy, this is children's lives, women's lives that we're talking about here, and we shouldn’t be letting our commercial interests get in the way of protecting the health of mothers and babies.”

Nestlé responds

While no companies were named in the report, Dairy Reporter invited the International Association of Infant Food Manufacturers (IFM) and several manufacturers to respond.

Nestlé backed the report’s reaffirmation that breast is best up to two years of age, where possible.

“This is why we support the WHO recommendation of six months exclusive breastfeeding, followed by the introduction of adequate nutritious complementary foods along with sustained breastfeeding up to two years of age and beyond," a company spokesperson said.

For infants who cannot be breastfed as recommended, infant formula is the only suitable breastmilk substitute (BMS) recognized as appropriate by the WHO.”

Nestlé proud of its progress

Although the company has been named and shamed several times for Code breaches, and is barred from joining NGO the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) for such transgressions, it defended its record.

“We voluntarily apply our own stringent policy when it is stricter than national Code in 152 countries which are considered to be higher-risk in terms of infant mortality and malnutrition; notably we are the only company to voluntarily restrict the promotion of infant formula up to 12 months of age in those countries.

“We were ranked first in the Access to Nutrition Index’s pilot sub-ranking of BMS manufacturers and we are the only infant formula company included in the FTSE4Good Responsible Investment Index which assesses company’s BMS marketing practices. We transparently report on our progress on our corporate website.”

Clever marketing

“Clever marketing should not be allowed to fudge the truth that there is no equal substitute for a mother’s own milk,” UNICEF chief of nutrition Werner Schultink said in the WHO’s press release.

In response, Nestlé said, “We are ready to work closely with the public sector and the civil society, as well as to play a leading role to support countries’ efforts to promote a conducive environment to breastfeeding.”

SNE response

Aurélie Perrichet, from Specialised Nutrition Europe, which represents the interests of the European specialized nutrition industry, including food for infants and children, said manufacturers are complying with the regulations and work with enforcement bodies to ensure this compliance.

“We believe that nutrition education is as critical once a child is born as it is before and during pregnancy. Well informed parents make better nutrition decisions for their infants. Every mother wants, needs, and has the right to be informed about all infant feeding options and to be supported in her decisions.

“Information on breastfeeding and formula feeding provided to parents must be fact-based and fully substantiated by scientific research. Access to information also ensures that parents who choose to use formulas will prepare and use it in a safe and appropriate manner.”

The spokesperson said formula makers had to grapple daily with the multitude of country regulations implementing the WHO Code.

“According to the WHO, only 39 out of 194 member states had passed laws reflecting all the recommendations made to member states under the WHO Code as of 2015. This results in a highly complex regulatory environment for companies and can lead to misunderstanding and differences of interpretation about the application of the WHO Code.

“We recognize that improving the industry’s BMS marketing policies and practices requires a lot more work by all stakeholders.”

Nestlé encourages stakeholders to alert it to potential illegality via its “Tell Us” reporting system.

“We investigate all concerns and have the most robust systems in place to responsibly market BMS.”

IFM response

The International Association of Infant Food Manufacturers (IFM) told DairyReporter its members were committed to the 1981 Code, and are committed to responsible marketing practices and operating in an ethical manner.

“In addition to respecting local laws and regulations, and in order to support countries in ensuring a consistent approach, since January 2014 all IFM members have committed to adhering to The Rules of Responsible Conduct (RRC), which set a common standard for IFM members to market their nutritional products in an ethical manner,” an IFM spokesperson said.

The group said nutrition education is as critical once a child is born as it is before and during pregnancy.

“Well informed parents make better nutrition decisions for their infants,” the spokesperson said.

“Every mother wants, needs, and has the right to be informed about all infant feeding options and to be supported in her decisions. Information on breastfeeding and formula feeding provided to parents must be fact-based and fully substantiated by scientific research.”