The two experts also discuss why there is still room for improvement for optimising production of ‘conventional’ probiotics and postbiotics, as well.

What is the relationship between ‘next generation probiotics’ (NGP) and ‘commensal microorganisms’?

Bart Smit: Next generation probiotics are novel functional microbes with beneficial properties. One of the more innovative sources is ‘commensal microorganisms’: microbes that live in or on the human body in ‘niches’, such as the gut, skin, oral cavity, etc. As we look to the next-generation of probiotics and nutraceuticals, increasing attention is being paid to the health benefits these commensal microbes can deliver: such as preventing, treating or curing a disease or condition. Because the bacteria come from the human body, they can have a more intense and diverse interaction with it, compared to more ‘conventional’ probiotics such as lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that come from foods.

How do you take an NGP from lab to production?

BS: It is important to ensure the viability and stability of the microorganism and the optimisation of the production process, as you upscale from the lab to a production facility or pharmaceutical contract manufacturing organisation (CMO). There are two overall stages: firstly, you need an ‘upstream’ process that gives you (ideally) a highly concentrated fermentation ‘broth’ containing billions of the microbes you want to use. Then you need to turn that into a stable end product (often a powder, but it can also be a cream) through a ‘downstream’ process that incorporates multiple steps and conditions.

Each microbial strain will have its ‘best’ set of conditions, both upstream and downstream. However, any change you make to one condition can impact the others, so you have to keep each of them in consideration at all times, and be prepared for a bit of back-and-forth. It’s a complex balance.

What are the production challenges of bringing an NGP to market?

Anneloes Groenenboom: Microbes can be hard to grow and maintain: these are living organisms that react and interact with their environment and with each other. By careful screening at an early stage of production, you can be sure you are selecting the best microbe: one that, for example, is easy to grow and keep alive. Furthermore, your bacterial production process must be reproducible and scalable, to optimise yields, shelf-life, cost-effectiveness, etc.

The industry has been working with ‘conventional’ probiotics such as LABs for a very long time, but NGPs are a much more recent addition. On the one hand, there is generally less familiarity with these organisms. On the other, in many cases they are simply more difficult to grow and work with. For example, they can have very complex nutritional requirements, and many are strict anaerobes, requiring a zero-oxygen environment to survive or replicate.

What factors can be adapted to optimise the growth and stability of an NGP?

BS: The composition of your growth medium, to start with. It must allow you to produce enough microbes for your purpose, whether testing (such as clinical trials) or commercialisation. But you have to balance that with other needs. For example, you must ensure your medium doesn’t contain allergens. In addition, plant-based media are preferred over animal-based, both for safety and for diversity of applications. However, NGPs such as commensal microorganisms come from very specific niches in the human body. You thus need to find ways to reproduce the niche conditions as closely as possible to get the best growth, then transfer the microbes to a non-animal-based niche.

AG: During the downstream process, the drying stage is where many bacteria are lost. So picking the right cryoprotectant (for freezing) or lyoprotectant (for freeze-drying) is key to the survival rate of your microorganisms. You can further optimise production and stability by identifying the optimal growth phase for harvesting, milling techniques, etc. And you can analyse the impact of downstream processes such as centrifugation, cross-flow filtration and formulation (liquid, powder or capsule).

What specific techniques can you use to speed up the development of a new probiotic?

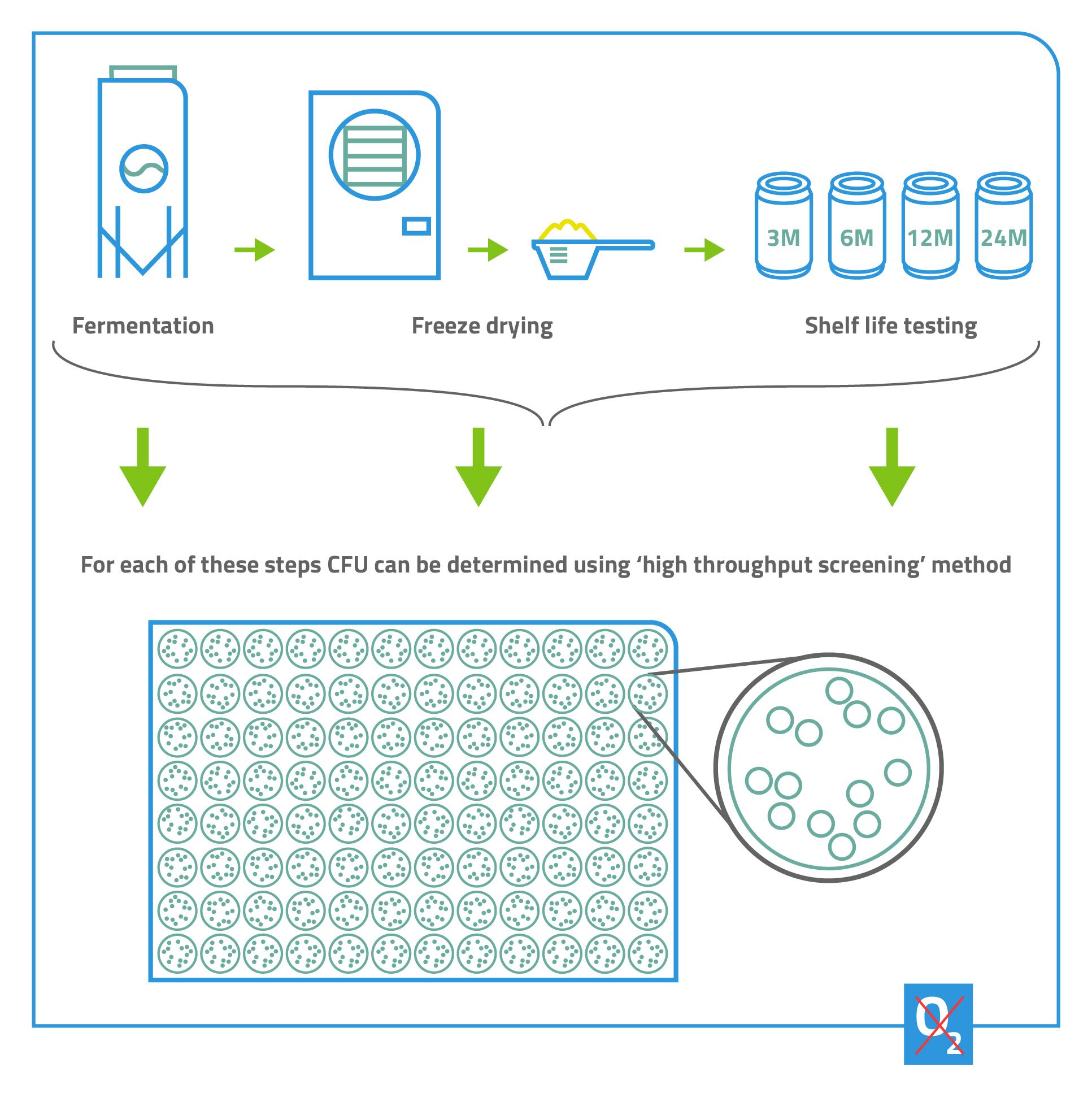

AG: High-throughput screening on the microlitre level enables you to test many different variables, in both the upstream and

downstream processes, quickly and cost-effectively. You also reduce the risk of focussing your resources on a microbe that, in the end, is not suitable for manufacturing.

For example, you can use high throughput screening to test media compositions, to determine which nutrients and micronutrients are essential for a specific organism’s growth. By doing this with different strains of the bacteria, you can also see which combinations of strain and medium give the best results. Downstream, you can use high-throughput screening to identify the best freezing or freeze-drying formulations.

Another useful technique is accelerated shelf-life testing, to test the stability of the various strains by seeing how they react to different temperatures and humidities. There are two different approaches you can use here. On the one hand, you can try to closely mimic the future application, to see how the probiotic will work under the expected conditions. But you can also ‘challenge’ the bacteria by putting it through more extreme conditions, to very quickly see which variation of protectant or strain is the best.

How do you choose which formulations and conditions to try?

AG: In biology there are always surprises, but you can minimise the risks and maximise the possibility of a positive outcome by using a science-based approach. When you are working with an unknown microorganism, you can’t test every possibility. So an understanding of microbiology, fermentation, food technology, etc. is essential to identify the best starting place. And during the journey, when a ‘creative’ step may be necessary, basing it on expertise and known principles can maximise the chance of success.

Can these techniques be used to further optimise culturing and production of more ‘conventional’ probiotics, and of postbiotics, as well?

AG: Absolutely! The overall approach is the same. For example, with the shift to the consumption of more plant-based protein foods, there is a call to transfer traditional probiotic strains from dairy-based to plant-based media, to they can be used in more applications. Furthermore, over the years there have been a lot of improvements in technologies like freezing and freeze-drying. So exercises such as running high-throughput screenings on nutrients or cryo- or lyo-protectants may enable you to find ways to produce higher yields or reduce microbe losses, even for a ‘tried and true’ probiotic. And keep in mind, everything here can be applicable to optimising postbiotics, as well.