People worldwide are living longer. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are approximately one billion people aged 60 years or over worldwide. This number is projected to increase to 1.4 billion by 2030 and 2.1 billion by 2050.1

Elderly subjects are often affected by more than one disorder at the same time, including hearing loss, eye diseases, diabetes, sarcopenia (muscle loss) and arthritis, as well as more severe and degenerative diseases affecting the nervous system.

The term inflammaging highlights the relationship between physiological ageing and the presence of a persistent, systemic, low grade inflammatory response which occurs without any clinical symptoms. This represents the basis for different chronic degenerative disorders commonly observed in the elderly.2

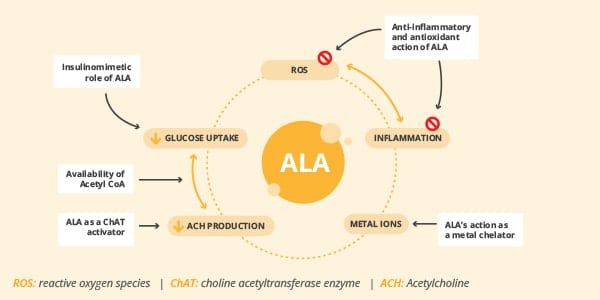

This condition is usually linked to an increase in oxidative stress with advancing age, resulting from an impairment of antioxidant defenses and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). High levels of ROS appear to play a central role in the development and progression of inflammation and cellular ageing. Sustaining a pro-oxidant status, which favour the onset and persistence of a chronic inflammatory process, ROS trigger a vicious cycle that further exacerbates the state of oxidative stress.3 Alpha lipoic acid (ALA), also known as thioctic acid, is a naturally occurring compound. It is synthesized in small amounts by the human body and is also found in many common foods such as broccoli, spinach and red and organ meats. Due to its biological activities, ALA may represent a promising nutritional strategy for protecting the human body from the damages of inflammaging (figure 1).

Figure 1. Biological activities of ALA (Adapted from 9)

While providing an anti-inflammatory effect, ALA is also considered to be a powerful antioxidant, playing a pivotal role in many physiological processes by neutralizing free radicals and ROS in both watery and fatty environments. Preclinical in vitro and in vivo assays demonstrate that ALA modulates different pathways of oxidative stress and attenuates nociception in animal models of diabetic neuropathy, peripheral nerve constriction injury, and associated pain.4

Nowadays, the health ingredient market faces a lack of ALAs suitable to be used in food supplement formulations that are backed by extensive data for effectiveness and safety in human subjects.

Relieving nerve pain and discomfort

BETTERAL® is a branded, food grade (solvent-free), premium quality form of ALA, specifically developed for the nutraceutical industry. It has over 14 years of scientific research behind it and more than 1,000 subjects involved in clinical trials in total, showing its safety and efficacy in supporting overall health and wellbeing.

Thanks to its very low content in polymers and optimized stability, BETTERAL® has been shown to be absorbed quickly and efficiently following oral intake by healthy subjects regardless of dosage forms and has a remarkable safety profile.5

As we age, the functionality of peripheral nerves naturally declines, contributing to occasional nerve aches and discomfort in the hands, feet, neck and back. This kind of discomfort may significantly impact the quality of life and everyday activities of affected subjects. Unlike the great majority of unbranded ALAs, the nerve protective effects of BETTERAL® have been confirmed by multiple human trials.6-8

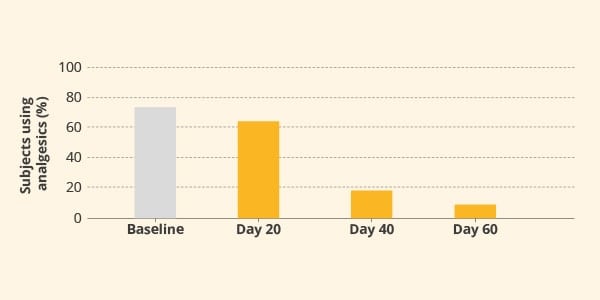

BETTERAL® (600 mg/day), in combination with superoxide dismutase (SOD), was administered for 60 days to 98 healthy subjects with chronic lower back pain (LBP) lasting at least six weeks. Pain perception and functional activity were assessed with the Pain Rating Scale (PRS) and Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ); the use of pain killer drugs was also recorded.

The treatment with BETTERAL® led to a significant reduction of analgesic drug use, from 73.5% at baseline to 8% of subjects at the end of the study. This result was a direct consequence of a better feeling, as well as improvement in perceived pain and functional disabilities (figure 2).6

Figure 2. Analgesic drugs used by subjects treated with BETTERAL® for 60 days. P<0.05 Day 40 vs baseline; P<0.01 Day 60 vs baseline.

Similar results were observed in a trial involving 96 subjects with chronic neck pain.7 The active group consumed BETTERAL® (600 mg/day) in combination with SOD, under a physiotherapy program, for 60 days. Participants under physiotherapy alone were considered as the control group. Interestingly, a significant reduction in the Visual Analogue Score (VAS) and modified Neck Pain Questionnaire (mNPQ) scores were recorded after one month of administration, compared to scores captured in the control group. Such improvement increased further at the end of treatment (figure 3).

Figure 3. Pain assessed by modified Neck Pain Questionnaire (mNPQ) after two months of treatment. The difference between groups was statistically significant (p<0.001).

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) is a neurological disorder characterized by pain and tingling in the hand, generally due to a compression of the median nerve. 112 subjects with moderately severe CTS were enrolled in a randomised trial and were treated for 90 days with BETTERAL® (600 mg/day) in combination with gamma linolenic acid (GLA) and vitamins, or a multivitamin preparation alone as the control group. BETTERAL®-based formulation was more effective in reducing symptom scores and functional impairment (as measured by the Boston questionnaire) compared to the control group receiving a multivitamin.8

BETTERAL® is a highly pure form of racemic ALA specifically created for those private label manufacturers that are searching for premium branded ingredients, either to increase consumer trust in their end products or to provide healthcare professionals with solutions backed by clinical research.

In order to offer greater formulation applications, BETTERAL® is available as a fine powder suitable for softgels or in ready-to-use granules ideal for tablets and capsules.

References

1. World Health Organisation. Aging.

2. Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E.; (2018). Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nature reviews. Cardiology 15, 505-522.

3. Hekimi, S.; Lapointe, J.; Wen, Y.; (2011). Taking a "good" look at free radicals in the aging process. Trends in cell biology 21, 569-576.

4. Viana, MDM.; Lauria, PSS.; Lima, AAD.; et al. (2022). Alpha-Lipoic Acid as an antioxidant strategy for managing neuropathic pain. Antioxidants. 11, 2420.

5. Mignini, F.; Nasuti, C.; Gioventu, G.; et al. (2012). Human Bioavailability and Pharmacokinetic Profile of Different Formulations Delivering Alpha Lipoic Acid. Open Access Sci Rep. 1(8):1-6.

6. Battisti, E.; Albanese, A.; Guerra, L.; et al. (2013). Alpha lipoic acid and superoxide dismutase in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 49(5):659-64.

7. Mauro, G.L.; Cataldo, P.; Barbera, G.; (2014). α-Lipoic acid and superoxide dismutase in the management of chronic neck pain: a prospective randomized study. Drugs RD. 14(1):1-7.

8. Di Gironimo, G.; Caccese, A.F.; Caruso, L.; et al. (2009). Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome with alpha-lipoic acid. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 13(2):133-9.

9. Triggiani, L.; (2020) Potential therapeutic effects of alpha lipoic acid in memory disorders. Progress in Nutrition. 22(1):12-19.