In previous articles, we have touched briefly on the benefits of fermentation for food safety, health benefits and the protein transition. Its key role in the dairy sector is undeniable, while its importance for developing plant-based products has quickly grown. However, selecting cultures, blending strains, and controlling the fermentation process is far from simple. To find out how to do that effectively, I spoke to Wim Engels, Senior Project Manager and expert in food fermentation for NIZO, who has over 30 years of experience in the fields of fermentation, chemistry, biochemistry and cheese ripening.

René Floris: What is fermentation, and what benefits does it offer the food industry?

Wim Engels: In food fermentation, live micro-organisms change the chemistry of a food ingredient or product through metabolic processes using enzymes. For food manufacturers, fermentation can:

- extend the shelf-life and safety of a food product

- add health benefits to the food, such as vitamins, (bioactive) peptides and probiotics, or help to reduce sugar, fat and salt levels

- provide a very pleasant depth of flavour and texture

And it does all this without added components or ingredients, supporting 'clean label' goals, for example.

RF: How is fermentation ‘designed’ into a food product?

WE: When developing a food product, there is rarely a single bacterial strain that will produce all the characteristics desired. Generally, we select a ‘starter’ culture that is responsible for the main fermentation, then add ‘adjunct’ cultures for specific flavours, textures, storage properties, etc. Creating this balance is very complex. Bacteria are living organisms that don’t always act how we want or expect. Different strains may do best under specific temperature or oxygen conditions, so you want to combine those that will grow and metabolise under the same environment. Finally, strains interact with each other, sometimes in undesirable ways.

You have to understand the starter bacteria and their metabolism: how they convert amino acids into compounds that contribute to flavour, texture, etc. This allows you to direct your combination of cultures, for example, if you want a ‘gouda flavour profile’.

Even then, the bacteria will likely act in unexpected ways. There is no decision tree that specifies ‘if you do A, B and C, you will definitely get result D.’

RF: How then do you test bacteria and strain combinations?

WE: Initial screening of a bacteria is generally done in laboratory media, but the behaviour may be different when we apply more complex substrates, e.g. dairy, plant protein-based emulsions, etc. Large-scale screening of characteristics such as fast acidification using existing culture collections can provide insight into suitable strains.

Testing the functionality of the micro-organisms in a ‘real’ food substrate, such as cheese, on a micro-scale can be a time- and cost-efficient step. Then you can scale up, to see how the processes impact the result. The behaviour and metabolism of the bacteria are strongly affected by their environment, so seemingly small changes in your processes can change the outcome significantly.

RF: How has fermentation helped food manufacturers solve real market needs?

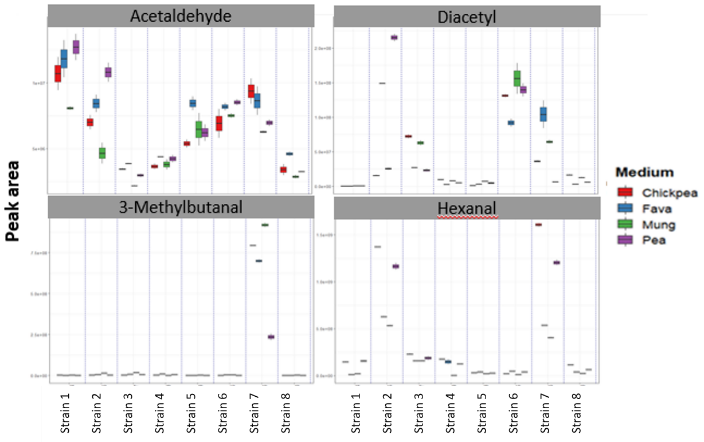

WE: Fermentation has been extensively used in the dairy industry for decades, and the process has become very sophisticated and tailored. For example, we at NIZO have developed strains with highly specific characteristics such as producing diacetyl for flavour or nisin for

preservation, reducing bitterness, tolerating temperature or pH ranges or performing on the surface of cheese. This gives product developers a huge toolbox to work with.

If you are developing a cheese with reduced fat or salt, for instance, you may have issues with taste, texture, contamination and spoilage. To solve them through fermentation, the focus is on selecting a starter culture that creates the appropriate conditions to enable a long shelf life (e.g. through fast acidification or producing antimicrobial compounds like nisin) and tuning the flavour and texture profile of the cheese, for example with appropriate adjunct strains. In this way, a cheese processing technology that enables full flavour development with less salt or fat can be developed.

RF: How does this knowledge of dairy fermentation translate for plant-based alternatives?

WE: To give one example, mould growth is a constant concern with plant-based cheeses – but can be addressed through fast acidification. This can be done chemically, e.g. by adding lactic acid, or with fermentation. Through our own research, we have shown that plant-based cream cheeses acidified through fermentation are more resistant to mould than those brought to the same pH with lactic acid.

Results such as these can be used to optimise processing strategies. However, you cannot simply ‘copy’ fermentation processes and mixes from the dairy world, because the bacteria will react in a different way to the plant-based substrate, which has different sugars, proteins, fat and moisture content.

RF: How can you ‘design’ bacteria that offer the characteristics you need, using accelerated evolution?

WE: Because bacteria grow so quickly, they can be adapted through repeated inoculation on the desired substrate. It is not fool-proof, but you can maximise the potential by starting with the best strain,

knowing what to expect and what result you want, and even using genome sequencing to control and monitor the micro-organism’s new metabolic capacities.

For example, if you want to create a soy-based yoghurt, there are two significant hurdles. Firstly, the complex sugars in soy are not ideal for fermentation by dairy lactic acid bacteria. Secondly, soy products tend to give a beany ‘off’ flavour that consumers don’t like.

To address these challenges, we have adapted dairy yoghurt cultures using accelerated evolution, growing them over and over on a soymilk substrate with frequent controls to check they were evolving in the ‘right’ way: converting the sugar, producing the desired flavours and textures. Within six months, we had a brand-new combination of cultures that could produce a drinking yoghurt with the desired smoothness and taste, with no or reduced ‘off’ flavours.

RF: How will fermentation knowledge-driven culture design improve the flavour of plant proteins?

WE: The broad potential of fermentation to improve the quality of plant-based proteins has been recognised by stakeholders at all levels who are initiating joint research to address the challenges. One example is the NIZO-chaired, public-private “Bio-purification of plant proteins” TKI Agri & Food project. It aims to develop generic fermentation processes to improve the flavour and texture of plant proteins and isolates.

Next month we will return to the protein transition, exploring methods to control pathogens in the chain, particularly for plant-based products.