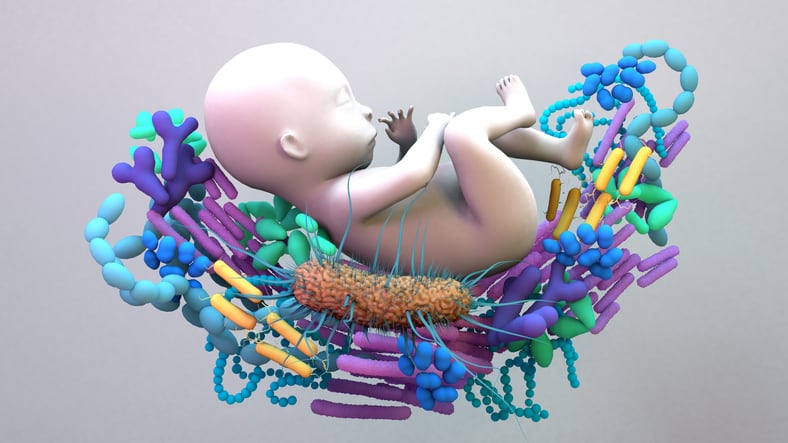

Data published in Nature Communications revealed a complex microbial ecosystem consisting of 115 previously unreported bacterial genomes exists among the Yanomami, one of the last remaining swidden (rotational farming) horticulturalist and hunter-gatherer communities minimally exposed to industrialization. They live in regions of Venezuela and Brazil.

“The fact that we identified these pristine microbiomes [among the Yanomami] to be so diverse wasn’t that surprising,” Dr. Juliana Durack, PhD, co-founder and executive director of the Holobiont Medical Research Foundation, told NutraIngredients.

“But what was, I think, the most surprising thing for me was to see the expeditioner gain microbial diversity when he was submerged into their lifestyle and really embracing the Yanomami lifestyle. We saw an increase in skin microbial diversity, and then upon return to industrialization, it plummeted.”

The expeditioner was researcher David A. Good, whose family is part Yanomami, but he has lived in the United States for most of his life. For the study, he traveled to the Venezuelan Yanomami community, his skin then a reflection of the western microbiome.

“There’s enough precedence out there to know that in our kind of modern world, chronic inflammatory conditions are associated with lower microbial diversity,” Dr. Durack said.

“Our modern skin has lost up to 80% of its microbial diversity, and with it very important functions that the microbiome used to do for us, including prevention of UV absorption and provision of metabolic support.”

Study details

The researchers took 94 skin samples for metagenomic analysis from 17 Yanomami between the ages of 1 and 70 years. During two expeditions, the researchers sampled the participants’ skin at seven different sites.

The expeditioner was also sampled at the same sites throughout his journey back to the United States. The researchers took 45 skin samples from him as well as samples from the Human Microbiome Project data archive to include in the analysis.

The researchers added that “further evidence of environmental influence on the Yanomami skin microbiota was observed from the longitudinally sampled skin microbiome of the expeditioner, who adopted the local practices in the daily activities of the Yanomami community.

“An increase in microbial complexity was noted in samples from combined sebaceous body sites at all three time points of collection in the Amazon (approximately one week apart) with bacterial richness, diversity and composition closely resembling that of Yanomami microbiota.”

The researchers took soil samples in areas where the indigenous people travelled and water samples from a creek and river near the Yanomami community to further understand the relationship between the Yanomami skin microbiota composition to the surrounding environment.

A Yanomami adult female traveler also returned to the United States with the expeditioner. Researchers collected samples from her body about two weeks into her extended stay in an industrialized setting, providing a contrast to the samples previously gathered while she was in her native Amazon community.

“The Yanomami cutaneous microbial community complexity diminished after integration into industrialized lifestyle, both in the microbiota of the expeditioner and a Yanomami family member who traveled out of the Amazon and was accompanied by loss of several bacterial genera, namely Dietzia, Kocuria, Micrococcus, Brevibacterium, Brachybacterium, Deinococcus, Yimella and Janibacter, all prominent members of the Yanomami cutaneous microbiota,” the researchers reported.

Their study not only assessed the abundance of beneficial microbes but also how they interacted.

“On the Yanomami skin, M. globosa formed a positive interaction hub, directly co-associating with several bacterial genera,” they wrote. “The relative abundance of M. globosa correlated positively with overall bacterial richness and diversity on the skin of Yanomami and western subjects. Collectively, these observations indicate that M. globosa relative abundance may be a marker of greater bacterial complexity in sebaceous skin microbiota and, perhaps, as a gatekeeper of skin health.”

The data suggest that these rich microbial communities may bolster skin barrier integrity, enhance lipid metabolism and provide greater resilience against oxidative stress—functions critical for maintaining skin health and possibly preventing inflammatory skin conditions common in industrialized societies.

Gaps in knowledge

The skin microbiome often takes a back seat to other microbiomes that have starring roles in scientific discourse.

“Everybody’s focusing on the gut, but a paper that came out last year said skin inflammation resulted in gut inflammation and changes in the gut microbiome, suggesting that skin and gut barrier are bidirectional,” Dr. Durack said. “What happens on the skin controls what happens in our gut and vice versa.”

Dr. Nathan Price, PhD, is a microbiome expert and co-director for the Center for Human Healthspan at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging. Commenting independently on the study, he said that it represents an exciting advance in the understanding of skin microbiome complexity, leveraging rare and precious samples from the remote Yanomami.

“The story of how obtaining these samples even became possible—through unlikely family dynamics and decades of time—is itself fascinating," he said. “Such communities, minimally exposed to industrialized lifestyles, provide a unique window into what the ancestral human microbiome may have been like, and its potential role in skin health through our evolution.”

Dr. Price added that there are “significant gaps” in current microbiome databases that are predominantly based on industrialized populations.

“These novel findings emphasize the urgent need for broader inclusion of diverse human populations in microbiome research,” he said, noting that the study’s insights into the Yanomami microbiome’s functional potential are particularly compelling from a scientific wellness perspective.

“Equally fascinating is the demonstration that immersion in this natural microbiome can temporarily reshape the microbiota of individuals from industrialized regions, suggesting practical avenues for leveraging environmental microbial diversity to promote skin health,” Dr. Price said.

“This research greatly enriches our understanding of what may constitute a healthy skin microbiome—and such diversity studies provide a crucial axis for discovery that simply doesn’t exist when studying microbiomes in industrialized populations alone.”

Source: Nature Communications. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-60131-7. “Yanomami skin microbiome complexity challenges prevailing concepts of healthy skin”. Authors: Juliana Durack et al.