Health claims are one of the most effective ways that dietary supplement companies can convey the benefits of their products. However, there are strict laws when it comes to health claims, and widespread confusion around how and when these laws come into play.

Writing in the journal Nutraceuticals, Spanish food regulatory experts described the regulation of dietary supplements as “one of the most complex topics in food law,” with health claims cited as one of the most misunderstood areas.

Health claims were unregulated in Europe until 2007 when the European Commission introduced a legal framework known as the Health and Nutrition Claims Regulation. The regulation governs the use of nutrition and health claims on food products, including dietary supplements, sold within the European Union.

The primary goal of this piece of legislation is to ensure that any claims made about a food’s nutritional or health benefits are truthful and not misleading to consumers. But what is the difference between a nutrient claim and a health claim?

Nutrient claims vs health claims

Kristy Coleman, legal director at UK law firm Ashfords and an AFN qualified nutritionist, said health claims are one of the most common queries brought to her by clients, often accompanied by significant confusion about the differences between health claims, nutrient claims and medical claims.

“A health claim is any claim that states, suggests or implies that a relationship exists between a food, or one of its constituents, and health,” she told NutraIngredients. “This includes any reference to a function of the body, mental performance or physiological effect.”

For example, “Vitamin C contributes to the normal function of the immune system” is a health claim, as is “Vitamin D contributes to the maintenance of normal bones and teeth”.

The wording is purposeful, using language that is clear and accurate, and does not exaggerate the potential benefits of the ingredient. The context in which the claim is used also matters, Coleman added, as well as any imagery, graphics and other creative assets.

Nutrition claims, on the other hand, relate solely to the composition of the product, such as ‘low sugar’, ‘source of calcium’ or ‘high in fiber’.

“A nutrition claim is any statement that suggests a food or supplement has particular beneficial nutritional properties due to the energy it provides, provides at a reduced or increased rate, or does not provide, or due to the nutrients or other substances it contains or does not contain,” Coleman said.

There are also certain thresholds in place for nutrient claims. For example, in the EU, a supplement or food item must contain at least 6 grams of fiber per 100 grams for the claim ‘high fiber’ to be used.

In contrast, a medical claim is any claim that a product can treat, prevent or cure a disease, including both physical and mental health. These claims are reserved solely for pharmaceutical drugs or medications and cannot be used for dietary supplements.

Types of claims

What is a health claim?

Any statement about a relationship between food and health.

What is a nutrition claim?

Any statement relating solely to the composition of a food product.

What is a medical claim?

Any statement that a product can treat, prevent or cure a disease. These claims cannot be used for dietary supplements.

Which health claims can be used? And what are the roles of EFSA and the European Commission?

In the EU, nutrition and health claims can be used only if they are authorized and appear in the annex to the Regulation and on the EU Register of Health Claims, which lists all permitted nutrition claims and all authorized and non-authorized health claims.

European countries which do not belong to the European Union have their own health claim registers. For example, British companies can use claims that appear on the Great Britain Nutrition and Health Claims Register, if the product meets the conditions of use.

The EU Register was devised by the European Commission, which reviewed hundreds of submitted claims by Member States before drawing up a positive list of established claims. The finalized first version of the list was published in 2012.

Any claims added to this list post-2012 have mostly been submitted by companies seeking a health claim for one of their own ingredients. Each claim is examined by EFSA and then reviewed by the European Commission and Member States.

“EFSA is a scientific advisory body,” food regulation expert Luca Bucchini told NI. “It assesses—among other things—health claim applications and new data and provides a scientific opinion to the Commission. EFSA does not approve or reject—it only provides a scientific opinion. However, in most cases, the Commission follows EFSA’s advice.”

The European Commission, on the other hand, proposes legal acts to Parliament and to the council.

“All minor legal acts, such as the list of authorized claims, approved novel foods and food additives, are made by the Commission,” Bucchini said.

“All acts of the Commission are approved by the experts of the Member States by majority. This means new health claims can only be approved if the majority of the Member States are on board. The decisions are of a technical nature, so objections are normally not political. Some Member States may, for example, prefer more warnings, or different conditions of use.”

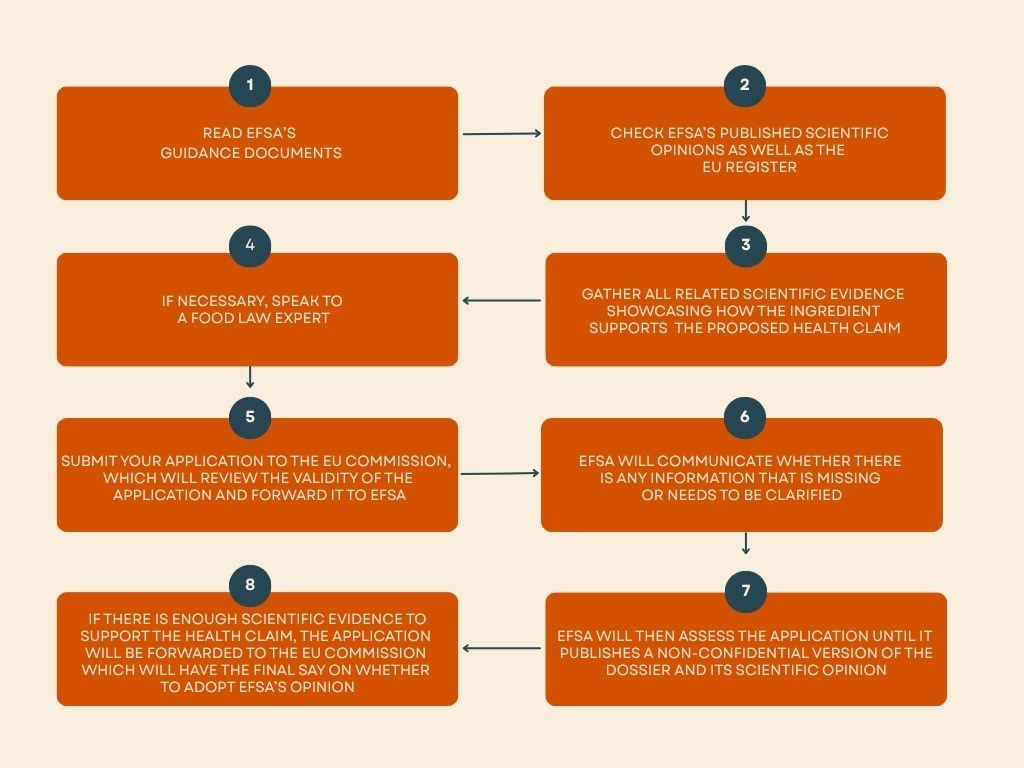

How to apply for a new health claim

Obtaining a new health claim is difficult, with EFSA estimating that around 70% of evaluated claims have been rejected due to a lack of scientific evidence. As of 2023, only around 260 health claims had been approved for use in the EU by the European Commission.

Nevertheless, ingredient companies can apply for a new health claim by submitting an application to EFSA. The type of application required depends on the type of claim the applicant is making.

Put simply, companies applying for functional claims will apply under Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006, while applications for disease risk reduction or children’s development will apply under Article 14.

There is a slight differentiation under Article 13, with 13(1) health claims supported by generally accepted scientific evidence. For example, “Calcium contributes to normal muscle function.” In contrast, 13(5) health claims relate to newly developed scientific research and/or protection of proprietary data. For example, “Tomato extract helps maintain normal platelet aggregation, which contributes to healthy blood flow.”

Generally, most functional health claim applications will now fall under Article 13(5) given that most health claims supported by generally accepted scientific evidence have already been approved.

Provexis’ tomato concentrate, marketed as Fruitflow, became the first product in Europe to obtain an approved health claim under Article 13(5) in 2009, with only a handful of 13(5) claims approved since.

“Article 13 claims are supposed to be conventional and not misleading because they are not related to any specific disease,” Katia Merten-Lentz, partner at Food Law Science & Partners told NI. “Importantly, most of them have been used all over Europe far before the adoption of the Regulation.”

“Article 14 claims are considered by the European Commission as the most dangerous for consumers,” she added. “They are related to a reduction of disease risk and can only be made where they have been authorized in accordance with the procedure laid down in Articles 15 to 18, which is the strictest procedure of the regulation.”

For example, an example of an Article 14 claim would be: “Calcium and vitamin D reduce the risk of osteoporotic fractures” or “Increased maternal folate intake reduces the risk of neural tube defects.”

It is important to note the difference between Article 14 health claims and medical claims. While medical claims, which are prohibited for food supplements, claim that a product can treat, prevent or cure a disease, companies can seek a claim that a product may be able to reduce disease risk under Article 14. However, this is the most difficult type of claim to obtain.

Types of health claims

Article 13(1)

Refers to functional health claims supported by generally accepted scientific evidence

Examples:

o Green kiwifruit contributes to the maintenance of normal defecation

o Sugar beet fibre contributes to an increase in fecal bulk

Article 13(5)

Refers to functional health claims supported by newly developed scientific research and/or protection of proprietary data

Examples:

o Tomato extract helps maintain normal platelet aggregation, which contributes to healthy blood flow

o Owing to its caffeine content, black tea improves attention

Article 14

Refers to disease risk reduction health claims

Examples:

o Calcium and vitamin D reduce the risk of osteoporotic fractures

o Increasing maternal folate status reduces the risk of neural tube defects

Use of health claims

The only health claims that can be used on the packaging of a product are those which are approved and appear on the EU register. Coleman said there is “very limited flexibility” when it comes to health claims, highlighting that the law applies not only to explicit statements but also to implied or indirect claims.

“This means that claims such as ‘feel your best’, ‘restore balance’ or ‘support your lifestyle’ may still be captured as health claims, depending on context,” she said. “If such phrases are used in conjunction with references to physiological effects or nutrients known to have a health function, they are likely to be considered implied health claims.”

The exact wording of the health claim itself is also an important aspect to consider, according to Merten-Lentz.

“The national authorities have a very strict approach and consider that the wording adopted by the European Commission must be precisely followed,” she said. “However, some national guidance—such as a Belgium’s and the UK’s—provide some useful examples of ‘tolerance’ when it comes to the way an authorized health claim could be slightly rephrased.”

Implying an unapproved health claim via imagery is also prohibited. This is because the European Commission defines a claim very broadly as “Any message or representation, which is not mandatory under Community or national legislation, including pictorial, graphic or symbolic representation, in any form, which states, suggests or implies that a food has particular characteristics.”

For example, products that use an image of the gut alongside a product aimed at gut health, particularly if placed alongside references to nutrients or well-being language, would constitute a health claim.

“This is often overlooked,” Merten-Lenz said. “It is very tempting to consider that a picture would be less legally harmful than a full message on a packaging, but this is not the case.”

Overall, Coleman highlights the importance of remembering that regulators assess the entire presentation of the product, meaning that the wording, imagery and branding will all be assessed.

“If, when taken as a whole, the combination of imagery and text implies a health benefit, it may be treated as a health claim,” she said. “If not authorized, such a claim would be unlawful.”

What are the risks of non-compliance?

Food law experts say one of the most common pitfalls for supplement brands and ingredient suppliers is assuming they can make a health claim based on results from a clinical trial that supports an ingredient’s potential health benefit.

Even if there is a wealth of scientific research to back up a specific health claim, if it is not on the EU Nutrition and Health Claims Register, it cannot be used.

“Scientific studies may not be used in consumer facing materials to justify unauthorized claims,” Coleman said.

“Even factual references to studies can constitute implied health claims if they suggest the product has a specific health benefit. It is possible to provide scientific material to healthcare professionals in a non-promotional context, but access to this content must be appropriately restricted. Where such material is used in consumer contexts, even with citations, it is likely to breach the rules unless the underlying health claim is authorized.”

Failing to comply with these rules can result in significant consequences, including hefty fines and requests to remove entire product lines from the market.

“It is clearly stated in the General Food Law Regulation 178/2002 that any food placed on the European market must be safe and compliant with all the laws in force,” Merten-Lentz said.

“Consequently, it means that in case a national authority of control challenges a claim considering it in breach of Regulation 1924/2006, they can formally ask the food business operator to withdraw the non-compliant products still on the market and to review the packaging of the ones in stock before placing them of the market. This is on top of fines for non-compliance.”

The severity of these fines vary from one Member State to another. Outside of the EU, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has recently been given new powers to issue fines of up to £300,000, or 10% of turnover, for non-compliance.

“There are also reputational risks and commercial consequences,” Coleman said. “Products may be delisted by retailers, removed from online platforms, or the brand may face negative publicity.”