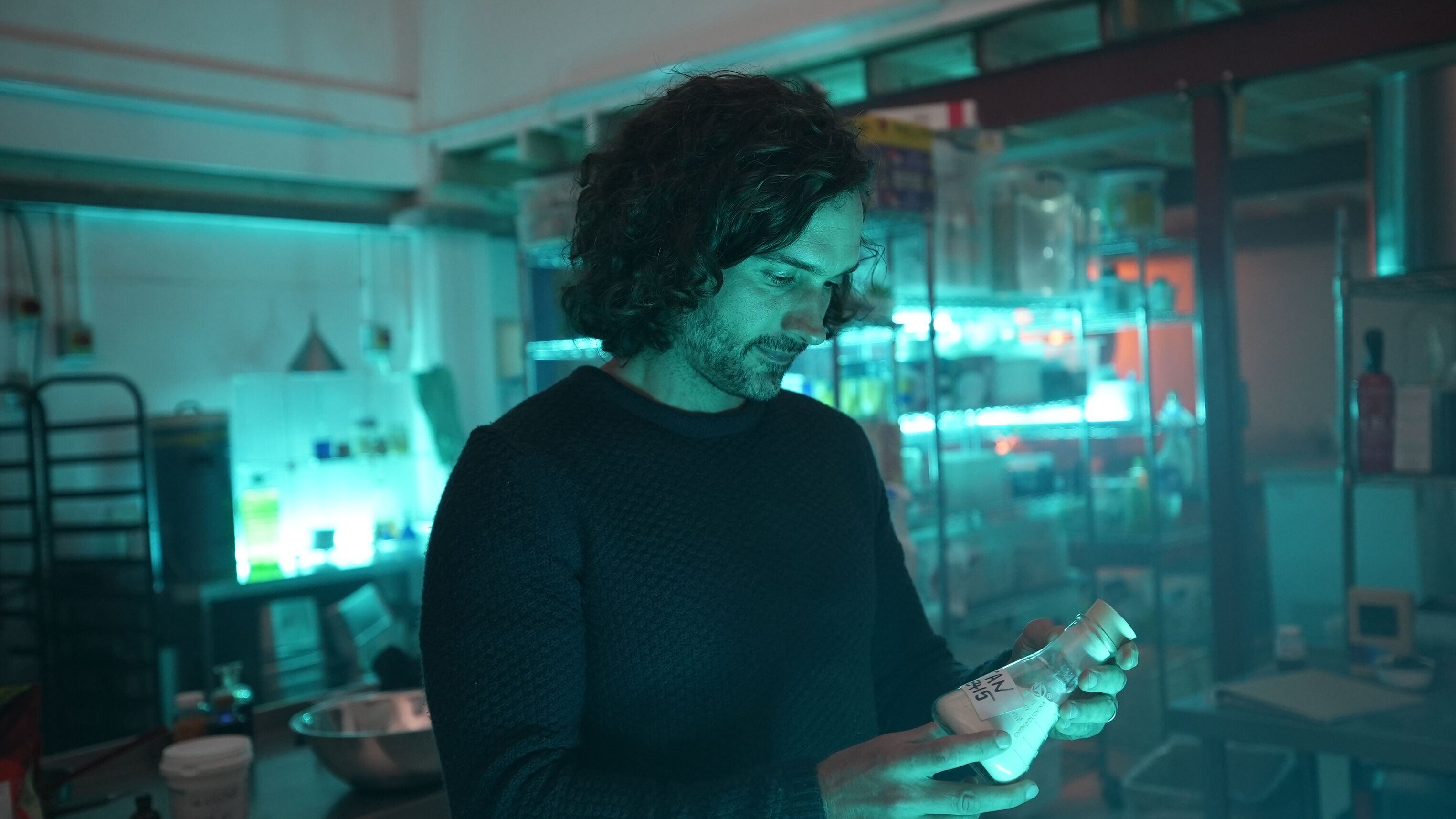

In the TV documentary titled Joe Wicks: Licensed to Kill, which aired in the UK on Monday, Oct. 6, the fitness figure teamed up with Dr. Chris van Tulleken, author of the book Ultra Processed People, to create the ‘UK’s most dangerous health bar’ in an aim to reveal the risks of UPFs.

The purpose of the documentary was to uncover “the harmful effects a diet high in ultra-processed food is having on our health and to pressure the government and the food companies to make some changes,” Wicks wrote in his LinkedIn post announcing the project.

However, some experts believed that the campaign made protein bars a scapegoat for what is a much more complex issue.

Joe Wicks’ Killer protein bar

Wicks’ Killer Bar provides 3 g of saturated fat, 6.9 g of sugars, 19 g of protein and 4.5 g of fiber per portion.

The ingredient list is deliberately lengthy, containing 27 vitamins and minerals which validate over 200 health claims, alongside palm oils, maltitol, xylitol, aspartame, sucralose, hydrolyzed whey and soy proteins, polydextrose, maltodextrin, emulsifiers, stabilizers and preservatives.

“This chocolate-orange flavored protein bar is bursting with flavor,” the Killer bar website reads. “However, excessive consumption may increase your risk of cancer, stroke and early death.”

But, as fitness influencer and nutrition brand founder James Smith told NutraIngredients, Wicks appeared to provide no studies, no data and no credible evidence to these claims.

Smith noted that for him, absolutist statements such as “protein bars are bad” ignore all context and nuance, and that unfortunately, in the field of nutrition, misinformation and disinformation often appeared tolerated without consequence.

He explained that substantiating the accusation posed a classic catch-22: To truly test Wicks’ claims, researchers would have to recruit a group of people to eat only protein bars for several months, alongside a control group eating normally. Smith said this setup would quickly create an ethical crisis because the protein bar group would risk malnutrition. In short, he said, a proper study would be impossible from the start.

Singling out protein bars

There are many UPFs that could have been selected as part of this campaign and so the Killer bar has caused a stir among some in the functional food scene for perhaps being an unfair target of scrutiny.

“If you wanted to make a satirical food, you’d go after genuinely bad foods like chicken nuggets, chips, crisps, etc.,” Smith said.

When it comes to the impact of the Killer bar and the documentary on consumer perception, Smith thinks Wicks’ campaign could backfire, suggesting that consumers may rally around protein bar manufacturers in solidarity.

“It’s a blatant hit piece,” he said. “I think people will show their solidarity and support to these protein bar manufacturers”.

Nick Morgan, managing director of the nutrition market data analyst company Nutrition Integrated, agreed that the approach taken by the campaign was “disappointing”.

“I don’t think it’s fair to single out protein bars in particular, but the stunt maybe needed some kind of example or ‘vehicle’,” he said.

The demonizing of protein bars might have seemed like an easy win by the campaign, but in fact, touched a nerve among many. It is a “very emotive category for people,” Morgan noted.

For him, the framing misrepresented protein bars by taking them out of context. Morgan explained that most brands did not claim that protein bars would make someone healthier but rather that protein bars could provide a better alternative to traditional chocolate bars—with less sugar, more protein, added vitamins and minerals.

However, Wicks framed them to suggest protein bars claim to be outright ‘healthy’ rather than simply ‘healthier,’ which was a subtle but important distinction, Morgan said.

“From an industry perspective, that distinction matters,” he added." Of course, on the consumer level, lots of people will argue that maybe the consumers don’t see that subtlety, that difference, that we believe is a credible approach to making products."

He believes the campaign’s approach was misleading, stating that while Wicks attempted to make a point, the approach failed to address regulatory flaws that could have been discussed with the government or relevant authorities.

“Two wrongs don’t make a right,” Morgan added. “His approach prevents him from truly making his point and ends up highlighting things that misrepresent the reality, and that’s the core issue.”

Finding the balance with UPFs

Nichola Ludlam-Raine, dietitian and author of How Not to Eat Ultra-Processed, told NI that although Wicks clearly means well in promoting public health, she believes he chose the wrong example.

“Ultimately, protein bars were designed as a functional food, not a whole food,” she said. “They can be a healthier choice compared to a standard chocolate bar, but they shouldn’t be marketed or perceived as a substitute for truly nutrient-rich foods.”

She noted that they can fit into a balanced diet if eaten occasionally and with awareness, and that the concern would be if they became a daily—or multiple times a day—staple for people and replaced whole foods in a person’s diet.

Addressing the long list of ingredients included in the bar, Ludlam-Raine explained it’s important for consumers to focus on what the ingredients actually are, instead of worrying about the length.

“Some items with a long list can be healthful, for example, added vitamins, minerals, live bacteria or fiber, whereas others can be possible ‘red flags’ to signal that a food should be enjoyed more in moderation, in the context of a healthy and balanced diet, like excess added sugars or lots of different additives which can make a product hyper-palatable,” she said.

She noted that the UPF conversation is still very much in a debate stage, and therefore over-simplifying the message could have detrimental outcomes on consumer health.

“Not all ultra-processed foods are created equal, and importantly, the latest research shows that not all UPFs under the NOVA level 4 definition are associated with ill health or disease—and many are, in fact, healthful,” she said.

Tonic Health backs call for label transparency

Founder and CEO of supplement company Tonic Health, Sunna Van Kampen, who recently launched a new podcast in collaboration with Channel 4 called “The Good, The Bad & Healthy”, says he understands the concerns but that they may be down to a misinterpretation of the aim of the project.

“Joe’s point isn’t ‘protein bars are bad’, it’s about transparency and creating a clearer and healthier food environment which will help people,” he said, referencing how Chile’s front-of-pack warning labels—similar to those that Wicks is campaigning for—led to a reduction of high-sugar food consumption by 23%.

“That’s not demonization; it’s informed choice,” he told NI.

A front of pack notice would allow time-pressed shoppers to learn in seconds, he said, and giving information to consumers would affect their purchasing patterns, in turn motivating manufactures to alter their formulations to appeal to their purchasing audience.

“The Killer headlines are provocative, which is exactly what the campaign was designed to do,” he added. “This isn’t blanket negativity; it’s information that can help people see the truth.”

Wicks responds to criticism

During the show, Wicks acknowledged the criticism of his provocative launch, saying critics have accused him of demonizing foods by implying that a single protein bar could cause serious harm. He argued his concern is the addictive nature of UPFs and how that can drive more frequent consumption.

“There are people saying I’m demonizing foods, and I totally agree that balance and moderation is the answer,” he said to camera. “But these foods are so difficult to resist that most people can’t eat in moderation, and that is why the system is broken.”

For Dr. van Tulleken, the protein bar was simply used as an example of a UPF to illustrate the larger mission.

“Our bar is the representative product for a system of feeding people that is really, really deadly for millions,” he said.