In the first study of its kind, researchers from King’s College London followed more than 3,100 twins for over a decade, analyzing dietary intake and urinary metabolites. These biomarkers confirmed that higher levels of polyphenol metabolites were associated with lower cardiovascular risk scores.

Lead researcher Ana Rodriguez-Mateos, professor of human nutrition at King’s College London, said measuring these metabolites provided a more objective and accurate reflection of dietary intake than questionnaires alone, adding to the robustness of the findings.

“Because this is an observational study, we cannot say polyphenol consumption causes these differences, but the patterns support the idea that diets rich in polyphenol-containing foods, such as tea, coffee, berries, cocoa, nuts, whole grains and olive oil, are linked with better heart health,” she told NutraIngredients.

The role of polyphenols in human health

Polyphenols are a large class of over 8,000 naturally occurring compounds found in many plant foods. Subclasses include flavonoids, anthocyanins and phenolic acids, which are known for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

These properties can help combat oxidative stress and inflammation and have been explored in a variety of health contexts, including metabolic health, cognitive function and healthy ageing.

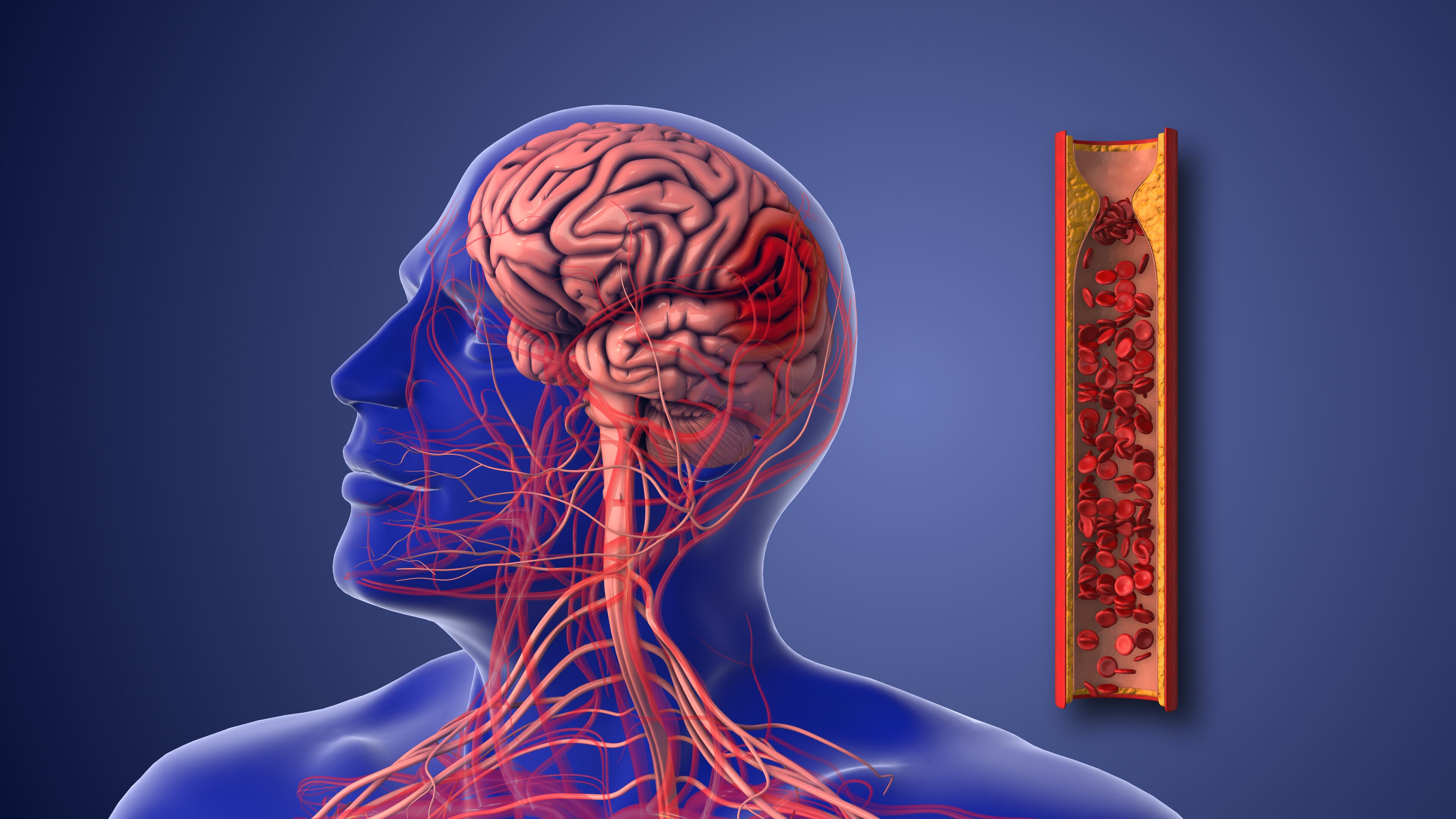

A growing evidence base suggests that polyphenols may also support cardiovascular health. Studies show that these compounds can improve the function of the blood vessel lining, helping blood to flow smoothly and prevent platelets from clumping excessively, reducing the risk of clotting.

However, researchers have historically struggled to accurately assess polyphenol intake in free-living populations. This is because most dietary assessment tools have not been validated for estimating polyphenol intake, and databases which provide nutritional information for foods often lack detailed information on polyphenol content.

To address these limitations, the researchers created a polyphenol-rich diet score (PPS), which characterizes diets based on intake of polyphenol-rich foods. They then compared these scores with a ‘metabolic signature’ and urinary polyphenol metabolites, making it the first study to comprehensively assess polyphenol intake and cardiovascular health using these methods.

How was the polyphenol-rich dietary score (PPS) developed?

The polyphenol-rich diet score was based on the relative intake of 20 foods, including tea, coffee, red wine, wholegrains, breakfast cereals, chocolate and cocoa products, berries, apples and apple juice, pears, grapes, plums, citrus fruits and citrus juice, potatoes and carrots, onions, peppers, garlic, green vegetables, pulses, soybeans, nuts and olive oil.

Participants were scored by the quintiles of their intake of each food group, with those in the highest quintile scoring 5 and the lowest scoring 1.

Diverse dietary intake linked to better outcomes

To conduct their study, the researchers asked participants to provide information about their dietary habits using the EPIC-Norfolk Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). This information was taken at baseline and towards the end of the study and then assessed to create individual PPS scores.

To substantiate the findings, random spot urine samples were collected from 200 participants and analyzed for metabolites. A metabolic signature of PPS was then established as an objective tool to assess polyphenol intake and reflect adherence to a polyphenol-rich diet.

Blood pressure and cholesterol readings were also taken, and an overall atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score and HeartScore were determined.

Overall, people who had higher PPS scores had a lower risk of heart disease. Specifically, a 10-unit increase on the PPS reduced the risk of heart disease by 8.5%, but even modest increases in polyphenol intake had a positive impact.

High intake of flavonoids and phenolic acids appeared to be particularly beneficial, with urinary metabolite analysis compounding these results. More granular analysis showed some specific metabolites from these compounds were associated with better heart health.

“Isoflavone metabolites, particularly daidzein, were negatively associated with CVD risk scores, reflecting soy intake,” Rodriguez-Mateos said. “Flavanone metabolites, including hesperetin derivatives, were positively associated with HDL-C, indicating citrus intake. Several phenolic acid metabolites, including hydroxybenzoic and hydroxycinnamic acids, as well as a tyrosol metabolite, mainly derived from olives and olive oil consumption, were negatively associated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

“Overall, these flavonoid and phenolic acid metabolites were linked with more favorable cardiovascular profiles.”

However, consuming a diverse array of polyphenol-rich foods was a better predictor of heart health than eating any single food or compound alone, suggesting a potential synergistic effect.

“Based on our findings and study design, we cannot definitively conclude that the stronger association seen with the PPS-D is due to synergistic effects of multiple (poly)phenols,” Rodriguez-Mateos explained. “However, the data suggest that the favorable associations observed are linked to the combined intake of diverse (poly)phenols within a varied diet, consistent with recent research showing that both the quantity and diversity of (poly)phenol consumption are important for heart health.”

Where next?

While the research is promising, particularly given the objective measures used to compound the results, Rodriguez-Mateos noted that additional studies in more varied populations are needed to substantiate findings beyond this study’s cohort of predominantly white middle-aged women.

“Further research is needed in more diverse populations, including men, other age groups, and different ethnic backgrounds,” she said. “Randomized controlled trials testing the effects of overall dietary patterns will be necessary to confirm these associations and inform inclusive dietary recommendations.”

Source: BMC Medicine. doi: 0.1186/s12916-025-04481-5. “Higher adherence to (poly)phenol-rich diet is associated with lower CVD risk in the TwinsUK cohor”. Authors: Y. Li, et al.