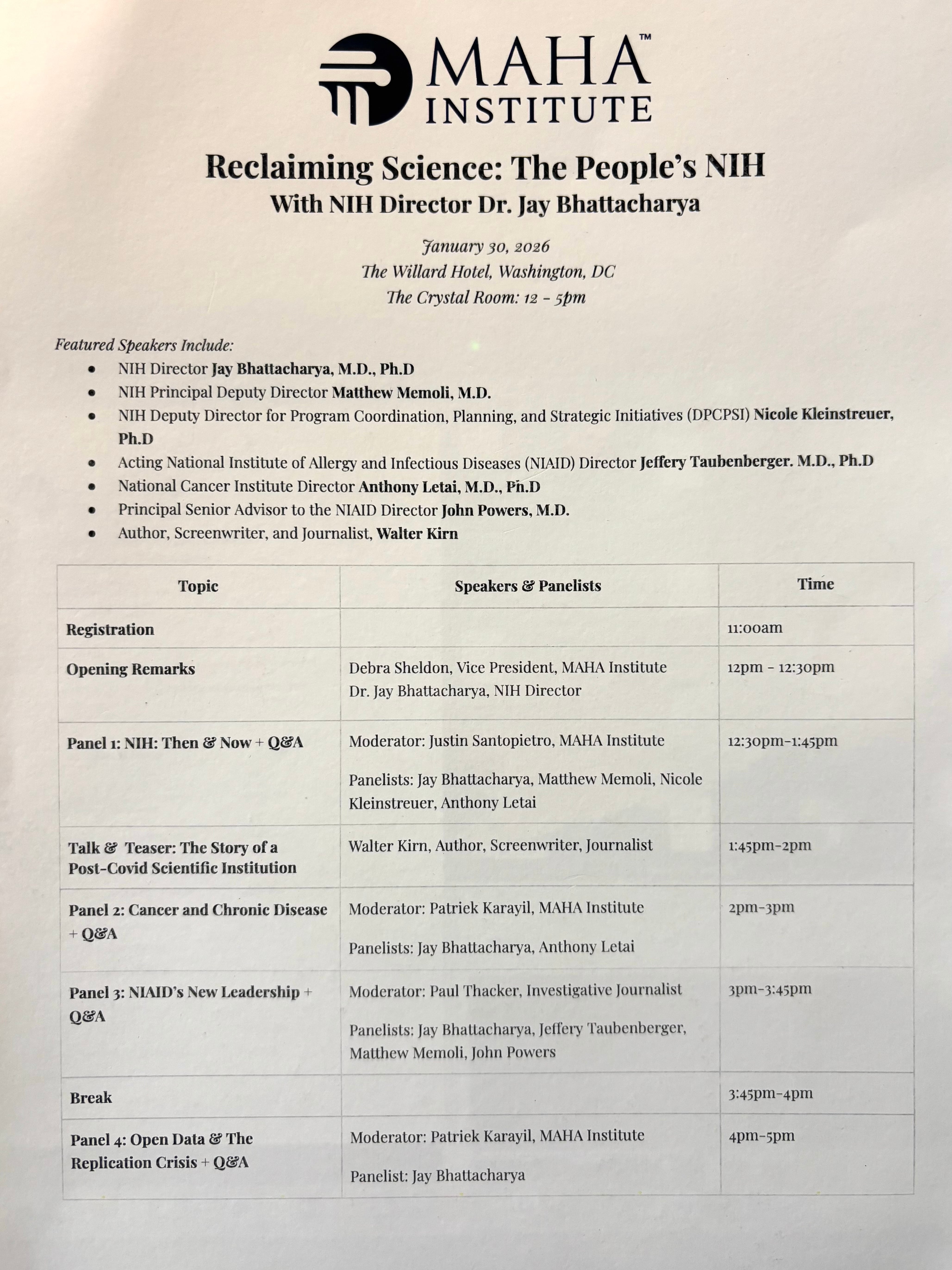

Cue the clapping from the standing room-only crowd in the Crystal Ballroom at the Willard Hotel that gathered Jan. 30 for The MAHA Institute’s “Reclaiming science: The People’s NIH” roundtable discussion headlined by Jay Bhattacharya, director of the National Institutes of Health.

“Let me talk about the MAHA movement for just a second because I think it’s really important to understand it,” he said. “It’s been the source of so much controversy, and part of the controversy has to do with the fact that it represents a seismic shift in the demands of the American people for the U.S. government to use its power and money for the purposes of improving health.”

Under the MAHA Commission mandate, the Stanford University health economist is tasked with leading a revolution at the NIH to restore the public health research institute’s commitment to gold standard science, tackling the chronic disease epidemic and restoring public trust and American research integrity through transparency, open data and replicable science.

“Chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes and obesity continue to cause poor health outcomes in every community across the U.S.,” Bhattacharya stated in an April 1, 2025 NIH release following his confirmation.

“Novel biomedical discoveries that enhance health and lengthen life are more vital than ever to our country’s future. As NIH Director, I will build on the agency’s long and illustrious history of supporting breakthroughs in biology and medicine by fostering gold-standard research and innovation to address the chronic disease crisis.”

The second revolution will not be politicized

Speaking at the event, American novelist and journalist Walter Kirn, who wrote the book that was adapted into “Up in the Air” starring George Clooney, gave a 15-minute presentation on the story of a post-COVID scientific institution.

At the center of this story was a preview of his current project “The Rash”, a satirical movie about the COVID era and a protagonist who stood up at a time of what Kirn has described as mass hysteria. That protagonist is loosely based on Bhattacharya, who surfaced in 2020 as a prominent critic of pandemic lockdowns and advocated for the “focused protection” of vulnerable populations rather than broad restrictions that harm society as whole based on inflated mortality rates. Nicole Shanahan, Robert F. Kennedy’s running mate in his 2024 presidential campaign, had suggested Kirn reach out to Bhattacharya for the assignment.

“If you don’t know the definition of ‘poetic justice’, […] I can give you a concrete definition, and I can give you a verbal one,” Kirn said. “The verbal definition is ‘the rewarding of virtue and the punishment of vice, especially in an ironic manner’. The concrete definition is Dr. Jay Bhattacharya.”

While Kirn likened Bhattacharya to George Clooney for his svelteness, salt-and-pepper hair, charm and eloquence, Bhattacharya’s predecessor, NIH Director Francis Collins, referred to him in a leaked email as a “fringe epidemiologist” who criticized the pandemic policies as responsible for devastating short- and long-term public health effects, particularly on children and the working class.

“Probably the biggest sin of the pandemic was the idea that it scientifically justified for us to treat our fellow human beings as mere biohazards,” Bhattacharya told the audience. “I mean, that idea is evil in and of itself, but when it had the imprimatur of science behind it, it was the root cause of so much of the upheaval that we saw during the pandemic.”

He argued that the “pandemic would have been bad regardless” but that the idea that scientists can order human action and interaction instilled the distrust that he believes led to a present moment of outcry by an American movement demanding to take back control of its health. While a 2024 PEW study found that public trust in scientists and their views in policymaking has rebounded to a 76% confidence rating since the pandemic, the “seismic shift” has cultivated the conditions for a second revolution that depoliticizes science.

“I want to launch the second scientific revolution,” Bhattacharya said. “The first scientific revolution basically took the truth-making power out of the hands of high ecclesiastical authority for deciding physical truth—leave aside spiritual truth, that’s a different thing—physical truth and put it in the hands of people with telescopes. It democratized science fundamentally, and the second scientific revolution, then, is very similar. The COVID crisis, if it was anything, was the crisis of high scientific authority getting to decide not just scientific truth—like Plexiglas is going to protect us from COVID or something—but also, essentially, spiritual truth.”

As such, he said the success of the reframed NIH will be making America healthy with “jaw-dropping advances” spurred by and replication of science that contributes to solving problems “that will actually make the lives of every single human being better.”

Reward through risk and replication

While NIH origins can be traced to 1887 and the one-room Hygienic Laboratory within the Marine Hospital Service in Staten Island, NY studying infectious disease like cholera and yellow fever, the agency—which today houses 27 different institutes—has grown from focusing on infectious diseases to covering all areas of biomedical research. Its long-time mission has been to enhance health, lengthen life and reduce illness through research.

In 2016, NIH formally adopted the motto “Turning Discovery Into Health” as the title and central theme of an NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2016-2020, the first consolidated plan to be published in its illustrious history. The plan’s overarching theme was to capitalize on scientific opportunities and address emerging heath challenges by turning research discoveries into improved health outcomes, while stewarding research investments responsibly.

Four core objectives sought to advance opportunities in biomedical research, foster innovation by setting priorities, enhance scientific stewardship through rigor, reproducibility and transparency in research, and excel as a federal agency by managing for results. Cross-cutting guiding principles focused on encouraging interdisciplinary and collaborative research, leveraging data science and emerging technologies, promoting diversity and workforce development and reducing disparities in disease burden and access to research benefits.

In many ways, the second scientific revolution is based on those same tenets, with Bhattacharya noting that “science takes time, and the government is a huge ship that takes a little while to move.”

In defining the proposed second scientific revolution, he is publicly advocating for the refreshment of science within the MAHA movement and ensuring the reproducibility of findings rather than finding truth in peer-reviewed papers published in top scientific journals by scientists who “get enamored” with their own ideas.

The second scientific revolution therefore emphasizes that science is inherently a collaborative enterprise that only slowly starts to understand truth and that the constructive way forward is to change the major basis of truth in science to replication—not “narrow replication but “broad science”. It is communicated as a “recommitment of science that welcomes scrutiny and demands reproducibility.”

“I think the right view is that most of the failure to replicate is actually in good faith,” Bhattacharya said. “It’s because science is hard. When different people look at the same problem, they give us different answers, and it’s a reason for further discussion, further conversation, further experiment to try to figure out who’s right and who’s wrong.”

Replication studies would then appear in a new open-access NIH journal, published out of the U.S. National Library of Medicine alongside the reference article “to encourage conversation.” There are also plans to introduce a native “replication button” on the PubMed search engine, supported by AI summary.

Another main driver of the revolution picks up on the NIH’s long-term vision to ensure that translational research efficiently converts lab findings into real-world treatments and health improvements. To achieve this, Bhattacharya shared that NIH is seeking to award new “high-risk, high reward” ideas early on, emulating Silicon Valley’s ‘productive failure’ culture.

“One really important thing about that is I do not want the government to decide what things should be replicated,” he added. “The government then could potentially be used as a weapon against new ideas, controversial ideas. I want the scientific community to determine the rate-limiting step ideas, the ideas that are the sort of pivotal, that if it turns out to be true, science moves one way, if it turns out to be false, science moves another way.”

In this scheme, grant proposals are siphoned through a newly established Simplified Peer Review Framework supported by a Unified Funding Strategy that eschews group think and strict paylines to promote applications from early career researchers that take intellectual risks to level the playing field and lower the crisis of care by advancing patient-centered, implementation science. While novel ideas are guaranteed a good hearing, Bhattacharya said the rigor of science must be applied to those ideas in a respectful way that substantiates claims with evidence from controlled study.

“Let’s make science great again,” Bhattacharya said, cueing another round of applause.